"To See the World Through the Guru's Eyes"

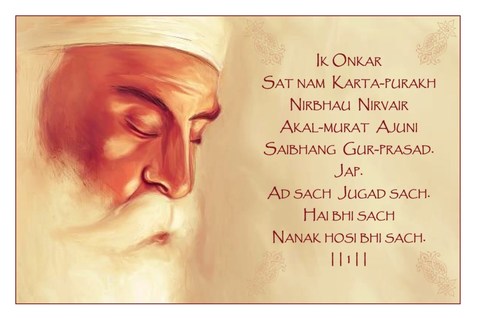

Mool Mantra & the Transmission of the Guru's Meditative Awareness

| article_with_endnotes.pdf |

The Sikh nation today is in difficult times. The Sikh community, once a beacon of humanity and inspiration for the world, today is a community much like any other. Alcoholism, spousal abuse, and drug addiction drag this nation down like every other, or worse.

Three hundred years ago, Guru Gobind Singh, the founder of the Khalsa, sang the praises of his greatest creation, the Order of saint-soldiers, but also warned that should they take up the way of mindless rituals and give up their distinctiveness, he would abandon them. Today, in fulfillment of his warning, the main preoccupation of Gurdwaras is the performance of rituals. Guru Granth Sahib is treated like an idol and ritual readings take place around the clock. Sikhs everywhere are complicit in this practice.

In describing the vitality of the Sikh nation in the present day, inventor and philanthropist Narinder Singh Kapany recently pointed to its growing numbers, the increasing quantity of Gurdwaras, the number of members in status-carrying jobs, and the array of schools and universities with programs that study Sikh dharma. This view is widely shared, using worldly criteria to measure the prosperity of the Sikh community.

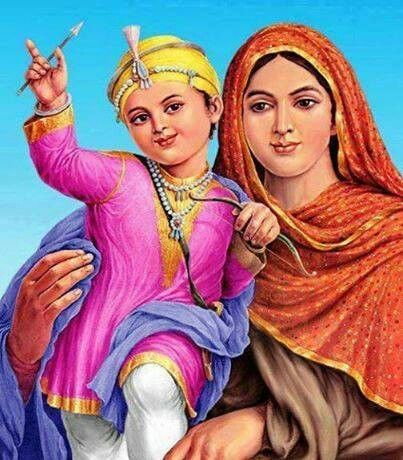

Another, opposing view is to judge the well-being of the global Sikh nation by its success in living by and sharing the inspiration of the Guru. Originally, the vitality of the Sikh community emanated from the practice of deep meditation, perfected and taught by the Guru. This practice was passed from Guru Nanak to Guru Angad and so on, unto the Khalsa. Children as young as five could achieve profound meditation and the mother played the unique role of Gurdev Mata, the first spiritual teacher of the newborn. The historic Guru’s mothers, wives, widows, and daughters – and through them, all Sikh women – enjoyed a personal connection with the great teacher and leader of the Sikhs.

All this unraveled in the 1700s and 1800s. In the mid-1700s, with the Sikh nation under threat, deep meditation gave way to martial exercises and everywhere, grown men came to predominate. With the passing of the guruship to Siri Guru Granth Sahib, both the care of the Guru and the transcription of new volumes was entrusted to men only.

The years of Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s rule in Punjab, witnessed a decline in the spiritual legacy of Guru Nanak. While temples were lavishly renovated and decorated, the Brahmanical rituals Guru Gobind Singh had warned of took hold in the maharaja’s court. In place of meditation, alcohol lubricated the affairs of state. In place of the high status and dignity women had enjoyed in a previous time, women were bought and sold in Ludhiana, prostitution prevailed in Amritsar, and female singers and dancers provided entertainment for the maharaja and his male guests.

With the spirit of Khalsa so compromised for so long, it should have surprised no one when the traitor Lal Singh decided the Anglo-Sikh War and the fate of Punjab for the foreigners. It should also have been no surprise that the young Dalip Singh, heir to the maharaja’s throne, was no spiritual prince. Coddled and sheltered from the world, he had not been educated in the Guru’s wisdom, to say nothing of ruling a kingdom.

In their colonial enterprise, the impressive British and their missionaries continued what Sikhs had already begun, further diluting and polluting their faith. While some Sikhs held back, others enthusiastically enrolled in British schools, joined the imperial army and civil service, and unconsciously picked up the tastes and habits of the conquerors.

This essay first took the form of a presentation given by the author at the International Sikh Research Conference at the University of Warwick in June 2017. It is intended as a wake-up call from the slumber of rituals, of religion for hire, and shallow representations of what is a uniquely inspiring and timely legacy at its root.

In these articles is a case study which it is hoped may convey the reality that children are not dumb passengers on the journey of spirituality. Rather, as Guru Harkrishan illustrated so well, children are fully capable of understanding and embodying the very best of human potential and possibility if only given a chance.

There are also a number of recommendations to help lift the Sikh nation out of the spiritual quagmire in which it finds itself today. There are recommendations on: spiritual training and education of the young, religious practice, spiritual culture, self-concept, spiritual sovereignty, and outreach. It is a long road from addiction and abuse, and a self-concept which is increasingly ethnic, to the glory of a sovereign, spiritual nation. But it is a road, in my view, that must be begun for the love of Guru, and must be begun now.

1. Meditation in Early Sikh History

Sikh dharma is historically rooted in the practice and experience of meditation. Roughly five hundred years ago, Guru Nanak (1469-1539) emerged from his illumination in the River Bein to announce to the world ‘there is no Hindu and there is no Muslim.’ In his lifetime, the founding Guru of the Sikh faith composed inspired verses termed Gurbani, many of which describe elements of the experience of deep meditation. Gurbani together with early Sikh history indicate that Guru Nanak conveyed his technique of inner communion to his disciples and that the practice of deep meditation continued at least to the time of the tenth Sikh master, Guru Gobind Singh (1666-1708). The historic record informs us of children adept at the practice of meditation during this period, the most famous being Guru Harkrishan (1656-1664), the eighth Guru, who ruled the hearts of his Sikhs from the age of five to his passing at eight years of age.

Meditation has a long history and a respected place in India’s spiritual and philosophical traditions. By contrast, Western scientists have just begun to study the practice of basic meditation. Comparisons of the benefits of short-term and longer-term contemplative practice are also just starting to be made.

Gurbani was composed by people who lived by meditation and encouraged the practice. Gurbani itself gives instruction to meditate. One of the most familiar directives to meditate is found near the beginning of the Anand Sahib of Guru Amar Das, recited at every Sikh spiritual gathering:

O my mind, ever dwell on God! (Siri Guru Granth Sahib, 917)

The ‘Sukhmani’ composed by Guru Arjan gives dozens of psychological, physiological and spiritual benefits related to the practice of Sikh meditation. One verse of several stanzas describes positive outcomes from even associating with a person who meditates. According to ‘Sukhmani’, one whose mind continually meditates has ‘realized the Creator.’

Their mind and tongue are animated by pure, intrinsic being and they see none other than that being.

Nanak says these are the qualities of one who has realized the Creator. (Siri Guru Granth Sahib, 267)

Through their meditative practice, the Sikh Gurus realized wisdom and forbearance. The first Guru built the foundation of a spiritual legacy. The second collected Guru Nanak’s Bani and continued his work. The third Guru expanded the community. Guru Ram Das managed conflicts in the community and founded Sri Amritsar. The fifth Guru compiled the Adi Granth and passed his spirit peacefully as a martyr. Guru Hargobind led his Sikhs to victory through four military attacks from the Mughals. The seventh Guru kept the peace. Guru Harkrishan lived as a saint and spiritual leader as a child. The ninth Guru stood nobly in the face of torture and death. Guru Gobind Singh opposed the bigoted Mughal empire and established Siri Guru Granth Sahib as Guru of the Sikhs from that time forward.

Not only the ten Gurus showed the powers of meditation. Sikh history tells of many Sikhs believed to have been divinely inspired through their practice of meditation. Numerous disciples of the Guru went as missionaries across south Asia. Many thousands of brave women raised their children as Sikhs in times of dire religious oppression. Thousands of men defended the faith, often against overwhelming odds, in the Guru’s armies. Bhai Kanhaiya achieved distinction by serving water to the wounded and dying without distinction of friend and foe. Then there were special cases such as Bhai Kaliana who healed the Raja of Mandi from incurable illness in the time of Guru Arjan and Bhai Jetha who, during Guru Hargobind’s time, relieved Emperor Jehangir of his fearful visions. According to Sikh tradition, some devotees offended the Guru through their thoughtless use of spiritual powers gained through meditation. At nine years, Baba Atal raised his playmate, Mohan, from the dead. Baba Gurditta revived a cow a Sikh had mistakenly shot and killed. Ram Rai performed miracles for Emperor Aurangzeb.

In the meditative culture that existed when Gurbani was composed, spiritual education could begin early in life. Baba Buddha was a boy when he met Guru Nanak and became his follower. The fourth Guru began his practice as a child when he was effectively adopted by Guru Amar Das. Guru Harkrishan rose to meditate alone each day before dawn by the age of five. The ninth Guru retired into nine years of meditation at the age of twenty-three. In Bachitar Natak, his autobiographical account, Guru Gobind Singh describes his parents’ prolonged devotions and his own tapasia in his previous life.

I performed such an ordeal of spiritual hardship there that I became one with the One.

My father and mother also meditated on the Unseen Being and practised many types of yogic sadhana. (Dasam Granth, 54)

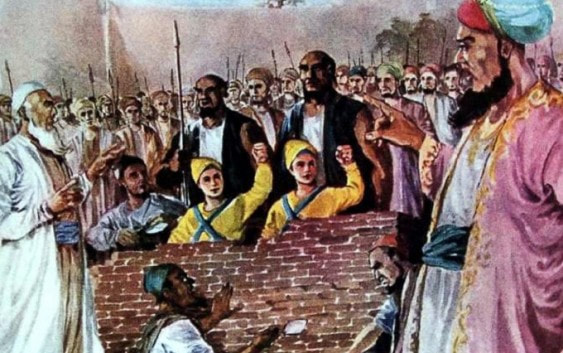

Through their meditation, Sikh children and youths acquired grace and inspiration. Guru Arjan Dev is believed to have composed ‘Mere Man Lochai’ when he was just 18 years old. Guru Hargobind took up the full responsibilities of being Guru at the age of 10 and Guru Har Rai at 14. Guru Harkrishan steered his way through difficult and dangerous circumstances, then peacefully surrendered his life during an outbreak of smallpox at the tender age of eight. Guru Gobind Rai graciously received the severed head of his martyred father and took up the leadership of the Panth when he was only nine. Bibi Bhani set the course of Sikh history by deciding how the guruship would be passed on while she was a young woman. Mata Gujri and Mata Jito both assumed their roles as Guru's wives at very young ages. At seven and nine, Baba Fateh Singh and Baba Zorowar Singh, spurned the temptations of Wazir Khan and embraced martyrdom.

Early Sikhs, their lives rooted in the daily practice and experience of meditation, prospered in challenging times. They experienced the blood of martyrdom and the gore of war. Despite every adversity, the community continued to grow and draw new members.

2. Depictions of Meditation in Gurbani

Deep meditation is not a part of everyone's daily experience. The saints who wrote Gurbani also devoted a good deal of their inspiration to depicting the details of their inner communion. They used distinctive terminology that may today be referenced as guideposts, allowing us today to navigate the sacred realm of profound meditation.

This terminology may be divided into four categories. Elements from each were freely combined, conveying several dimensions of the sublime reality of meditation. These categories are:

1) Conceptual: Terms such as ‘the One,’ duality, three gunas, ‘three worlds’ (animal, human, divine), turiaa, the ‘five thieves’ (lust, anger, greed, pride, attachment), and samadhi situate the meditative experience within parameters and using definitions found in Indian tradition of philosophy and psychology.

2) Locational: Terms such as the ‘tenth gate’ (at the top of the head), the ‘city of Shiva’ (the brain), the forehead, tribeni, ‘lotus of the mind,’ and ‘cave of being’ (the skull), describe that experience as it relates to physical and metaphysical aspects of the body.

3) Physiological: The main physiological reference in Gurbani is to the ‘flow of amrit (ambrosia).’ While open to interpretation, these references readily correlate with the brain's secretion of gamma-aminobutyric-acid (GABA), dopamine, melatonin, and other neurochemicals associated with meditation.

4) Subjective: Terms such as the anahat Shabad (unstruck Word), shun (neutral mind), anand (spiritual bliss), surat (meditative awareness) and nirvana depict purely subjective components of the experience of deep meditation. Not much can be objectively said about these. Kabir describes the ineffability of meditative experience to a mute person’s experience of eating sugar. How can they ever communicate what they are experiencing?

This terminology occurs many hundreds of times in Gurbani. Following are a few excerpts of this genre which demonstrate both the richness of the artistry and the continued passing on of the experience of meditation from Guru to disciple.

Guru Nanak:

Through meditation on the Creator, the lotus of the mind has come upright.

Amrit pours from the sky of the tenth gate. The Lord himself pervades the three worlds. (Siri Guru Granth Sahib, 153)

If the invisible could be seen with these eyes, it would surely be seen. And without seeing, there is no use in speaking of it.

The enlightened one spontaneously sees what others do not and serves with a meditative awareness. (Siri Guru Granth Sahib, 222)

Leaving off schemes and contentions, in the city of Shiva, the Yogi takes up his meditative posture.

The horn of the unstruck Word constantly makes celestial music, day and night in perfect tune. (Siri Guru Granth Sahib, 360)

The enlightened one lives free in the pristine cave of being.

There, using the power of the Word, he does away with the five thieves. (Siri Guru Granth Sahib, 904)

With their mind easily absorbed in the samadhi of the neutral mind,

Giving up selfishness and greed, they recognize only the One. (Siri Guru Granth Sahib, 904)

Guru Angad:

There are nine gates to the body castle. The tenth is kept well hid.

That stubborn gate is shut tight, but with the Guru’s Word it opens. (Siri Guru Granth Sahib, 954)

Guru Amar Das:

From being lost in the grip of the enchanting three gunas,

The enlightened one realizes turiaa, the fourth state. (Siri Guru Granth Sahib, 30)

Guru Ram Das:

There are nine gates. Tasteless is the taste of these nine openings.

Amrit is extracted from the tenth. (Siri Guru Granth Sahib, 1324)

Guru Arjan:

The jewel that was hidden has been found. It has appeared on my brow.

Beautiful and holy is that place, O Nanak, where you dwell, O my dear Lord! (Siri Guru Granth Sahib, 1096)

Guru Tegh Bahadur:

Give up praise and blame. Seek instead the state of nirvana. Servant Nanak says, this is such a difficult game.

Only a few enlightened ones understand it. (Siri Guru Granth Sahib, 298)

In this selection of quotes, we see a variety of depictions of inner awareness using conceptual, locational, physiological, and subjective terminology. While this Gurbani may sound mystical and strange to anyone unfamiliar with the vocabulary, to a meditator they are masterful expressions and directions on the path of inner experience.

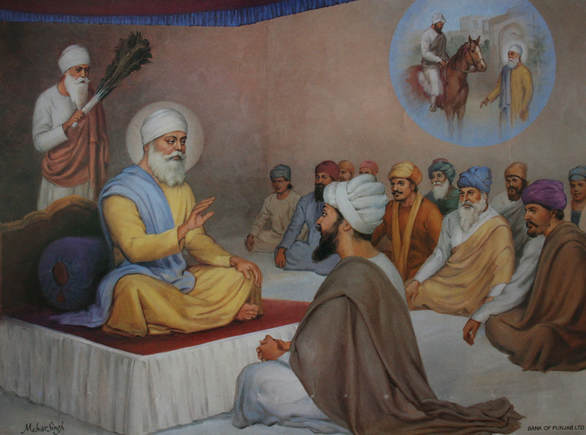

3. The Transmission of Meditative Awareness

The passing of meditative awareness from Guru to disciple ensured spiritual continuity through the crucial centuries of the founding of Sikh dharma. Every Guru, from the first to the tenth, instructed his disciples in meditation. In their life, each of them also lived as an example of meditative awareness. At the end of every Guru’s life, he was then bound to choose the best among his disciples to take up his duties. The repeated and unfailing passing on of the discipline together with the virtues of guruship ensured the transmission of the living inspiration of Guru Nanak through succeeding generations.

The Mool Mantra was central to the passing on of the guruship. Indeed, it expressed the mool (root) of Guru Nanak’s teachings. According to historian Max Arthur MacAuliffe and his learned teachers, the first Guru communicated the Mool Mantra to Bhai Lehna, who would soon become his successor, only after he had passed Guru Nanak’s last test.

In Gurbani, the idea of paaras, the ‘philosopher's stone’ that converts ordinary stone into gold, is used to describe the personal changes exacted by the Guru. In the following verse known as a Vaar, Bhai Gurdas (1551-1636 CE), the writer of early Sikh history, describes the relationship of spiritual transformation uniting Guru and disciple.

In creating the philosopher's stone, lies the greatness of the philosopher's stone, the enlightened one.

As a diamond is beautifully cut and shaped by another diamond,

The Guru's illumined awareness brings out the light of consciousness in his disciple.

At one with the Word, like a musician at one with their instrument,

Guru and disciple, disciple and Guru, become one and the same.

From one being, another came to be. It was ultimate being. (Vaar 9:9)

Elsewhere, Bhai Gurdas says:

From the Guru’s instruction, disciples are made, but rarely does the Master make a second Master.

One who gives their mind to the meditative consciousness of the Guru becomes like God. (Vaar 13:2)

As in Bhai Lehna’s case, the disciple’s consciousness was not only reshaped and transformed by the Guru’s grace, the disciple was also awarded the duties of guruship at the Guru’s passing. The following Gurbani, composed by Kal, a musician at the Guru’s court, describes the passage of the guruship, described here as the ‘throne of raj yoga,’ from Guru Nanak on to his successors, up to Guru Ram Das, the fourth Guru.

First Guru Nanak, like the moon, filled the world with bliss. He liberated humanity with his illumination.

Guru Angad was blessed with the treasure of divine discourse and knowledge of God.

He overcame the five demons and so was freed from the fear of death.

Guru Amar Das, the great and true Guru, is the preserver of honour in this age of depravity.

Seeing his holy feet, one’s regrets and shortcomings are erased.

When his mind was in every way satisfied, he was pleased

And bestowed the throne of raj yoga on Guru Ram Das. (Siri Guru Granth Sahib, 1399)

This verse depicts the journey of self-purification and self-realization under the guidance of the Guru. It focuses first on the efforts of Guru Nanak’s most worthy disciple who eventually succeeded him as Guru Angad. Through meditation, he overcame his ‘five demons’ (also ‘five thieves’) of lust, anger, greed, pride and attachment. Before attaining the guruship, Guru Amar Das’s best disciple needed to satisfy his Master’s mind ‘in every way.’ Only then could he receive the throne of raj yoga and become Guru Ram Das.

Bhai Gurdas Singh wrote a similar Gurbani celebrating the relationship between Guru and disciple. It begins:

God created the throne of true being in the gathering of the true.

Nanak, the fearless and formless, plays among the fearsome yogis!

Later in the same Gurbani, Bhai Gurdas Singh describes the contemplative practice of Guru Har Rai, the seventh Guru:

The seventh Guru, the limitless Har Rai, who meditated with a neutral mind and realized oneness,

Raising the sky of his awareness, and finding unity in the cave of his mind, sat and felt unwavering samadhi.

The refrain of this well-known composition goes:

Great, great is Gobind Singh, himself the Guru and disciple!

Guru Gobind Singh composed Khalsa Mahima to celebrate the greatness of the Khalsa. In it, he repeatedly describes the oneness between himself and his devoted disciples, using various images and relationships:

Khalsa is my special form. I live in the Khalsa. Khalsa is my face and limbs. I am ever, ever with the Khalsa.

Khalsa is my heart’s love. Khalsa is my fame and renown. Khalsa is my past and future. Khalsa is my joy and happiness…

Khalsa is my complete true Guru. Khalsa is my fearless friend. Khalsa is my wisdom and knowledge. Khalsa is always in my thoughts…

In the end, having gone on for many lines, the tenth Guru places but one condition on his relationship with the Khalsa:

So long as Khalsa remains distinctive, I will bestow on it all my glory. But if they follow the way of the ritualists, I will not keep them in my faith.

The passing of the Guru Nanak’s meditative mind to Guru Angad, and continuing from Guru to most worthy disciple over several lifetimes, guaranteed the continuity and integrity of the Panth. Guru Gobind Singh expressed great pride and joy in his oneness with the Khalsa, the creation of two hundred years of growth and transformation. The Guru’s mind and heart lived on in the Khalsa. However, the tenth Guru also warned that if his Sikhs should ever leave his unique way of life and take up the path of Brahmanism, he would no longer support them in any way.

4. From a Golden Age of Meditation to the Present

A long view of Sikh history reveals a golden age of meditation from the time of Guru Nanak to the battle of Bhangani Sahib (1688). The best evidence for this exists in Gurbani, which has already been discussed. A second source is the accounts of the Guru and his Sikhs in this period.

During this period, the vitality of the Sikh community emanated from the practice of deep meditation, perfected and taught by the Guru. Children as young as five could achieve profound meditation and the mother played the unique role of Gurdev Mata, the first spiritual teacher of the newborn. In this era, the Guru’s mothers, wives, widows, and daughters – and through them, all Sikh women – enjoyed a personal connection with the great teacher and leader of the Sikhs. Tradition tells us that Guru Hargobind taught: 'Woman is a man's conscience and money his servant. Children carry forward one’s lineage.'

Generally speaking, the period from 1688 to the second half of the 18th century was a period of great violence and social upheaval. With widescale persecution and invasions, sheer survival would have been priorities. This is evidenced by the codes of living called the rehitnamas written in this period which focus on keeping Sikhs together, rather than meditation.

With the Sikh nation under threat, deep meditation gave way to martial exercises and everywhere, grown men came to predominate. With the passing of the guruship to Siri Guru Granth Sahib, both the care of the Guru and the transcription of new volumes was entrusted to men only.

From the late 18th century to the start of the first Anglo-Sikh war (1845) was a period of relative peace in Punjab, where most Sikhs still lived. It was a time of prosperity and building of Gurdwaras, but not a period of inner meditation and inspiration. Rather, the time of the Sikh kingdom of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, from 1801 to 1839, when the Harimandir (aka ‘Golden Temple’) in Amritsar was famously covered in gold, is described by a number of historians as a period of inner decay. Brahmanical rituals which were introduced in the maharaja’s court as an aspect of stately decorum, spread into everyday use in Sikh households. Many new Sikh converts from Hinduism kept their Hindu customs and thinking, thereby affecting the Sikh community as a whole. While women’s situation may have improved in the early years of the Panth, devout Sikhs were shocked to learn of the sati, the burning alive of four of his queens and seven maid servants at the funeral of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Neither the families of the Gurus, the Bedis and Sodhis, nor the religious teachers, the Nirmalas and Udasis seemed to mind the deteriorating situation. Rather, most were comfortable with their new social status and wealth in the maharaja’s kingdom.

The British period (1846-1947), partition and Indian independence (1947), together presented new challenges of marginalization and dilution of the faith. The late 1800s was marked by two reform movements, the Nirankaris and the Namdharis, dedicated to purifying the faith. In the twentieth century, famous saints like Sant Baba Attar Singh, Sant Baba Nand Singh, and Bhai Randhir Singh, all known for their vigorous meditative practices, responded with movements of spiritual renewal. In the late 1900s, Siri Singh Sahib Harbhajan Singh Khalsa exported Sikh practices from India and helped gain recognition of the Sikh faith. He also taught meditation as a science and encouraged its scientific evaluation.

With the growing toll of stress and mental illness in the world today, one might think this to be an ideal time for the study of meditation. While the field of meditation research currently is dominated by the study of Buddhist and Hindu practices, Sikh dharma also has a vibrant contemplative tradition which may be explored. As there are no external physical threats to Sikhs individually and collectively today, the 21st century offers the opportunity of a second golden age of meditation.

A more pessimistic view of the present-day disconnect between Sikhs and their tradition of deep meditation recognizes the current conditions of the Panth and its focus on the realization of external objectives, together with its embrace of rituals and abstract theology, as a state of spiritual decay. Moreover, alcoholism is, and has for some time been, rampant among Sikh men. Drug addiction has also become common among Sikh youth, especially in Punjab. Gurbani vividly describes the world in a state of duality and decay:

In the Kal Age, there in no integrity and no course of truthfulness. Holy places are desecrated and the world is drowning in delusion.

In the Kal Age, God’s Name is the medicine. Closing their eyes and plugging their noses,

Humanity has descended into thuggery. Holding his nose shut with his fingers,

Man thinks he is seeing the three worlds, but he does not see even what goes on behind his back.

What a wonderful meditative posture is this!

The warrior class has abandoned its sacred duty and has taken up the language of the enemy.

There is no place of honour or honour of place in this world, and none considers right and wrong.

The scholars are polished in grammar and book-knowledge. Refined is their knowledge of sacred texts.

Without God’s Name, none is free, says Nanak the Lord’s slave. (Siri Guru Granth Sahib, 662-663)

As in yesterday’s situation, those who should be defending the faith have instead taken up habits at odds with a culture of meditation. Today as well, there are scholars polished in the language of Gurbani, but lacking in self-knowledge and inspiration.

Some thoughtful Sikh authors have described this era of dysfunction and decay. While these critics do not discuss meditation and the passing on of spiritual discipline, they criticize the religious administration in Amritsar. Writer and intellectual Kharak Singh states:

Leaders follow a policy of concentrating on politics alone; religious issues are not on their agenda… Not many among its elected members (or those who decorate Teja Singh Samundri Hall at its General Meetings for a few hours in a whole year) have religious scholarship or knowledge of Sikhism as their strong point… Resort to liquor distribution and other unfair means during elections are common knowledge… The challenges, unless adequately resolved, constitute a serious threat to the integrity and future of the Sikhs.

Two hundred years in its formation, the last three hundred years have been filled with trial and difficulty for the Sikh nation. After a half century of persecution and invasions, the wealth and relative peace of a Sikh kingdom only weakened the spirit of Khalsa. This is when ritualism entered the Panth. The status of women generally declined. Neither children nor women any longer played any valuable role as teachers or keepers of the faith. British colonialism and colonial habits then took another jab at the inner life of the Sikh nation. The impact of the British was such that, seventy years after their departure, Western ways of thinking and dressing still dominate in Punjab and the diaspora. Like most British children, Sikh children are not typically encouraged to meditate or to reach for spiritual glory. Their parents want them to be a Western doctor or lawyer, not a saint-soldier. Even the students of Sikh schools are pressed to compete academically without detailed instruction in meditation and self-development.

5. Changing Characteristics of the Sikh Nation

This paper is based on the observation that the transmission of meditative awareness is no longer at the centre of Sikh practice. Numerous apparent changes in the historic vitality and integrity of the Sikh Panth may be traced to this development. In this section, we will briefly examine changes that have occurred in five aspects of Sikh culture: spiritual training and education, practice, culture, self-concept, sovereignty, and outreach.

5.1 Spiritual Training and Education

As we have previously seen, during the formative years of Sikh dharma, its leadership frequently emanated from its youth. From these examples, we can assume that spiritual training and education began very early in life.

Today however, Gurdwaras are typically administered by senior members of the community with minimal concern for the spiritual needs of children and youth. The ignorance of the soulful potentialities of the young and the neglect of their spiritual training may be partially attributed to the dominant secular educational model. Rather than focussing on character development, secular schooling gives training in skills designed to give a person an edge in an increasingly competitive, technology-driven world. As members of a religious minority and often as immigrants, Sikhs are particularly vulnerable to pressures to compete and be materially successful.

Several writers have described the shortcomings of Gurdwaras in passing the Sikh spiritual tradition to new generations. Most of these studies focus on emigrant communities in the West, but the dynamic is practically identical in Punjab. A common issue is a confusion among parents between those values and practices which are religious and those which are merely cultural. One generally shared frustration among

youngsters is that they feel they cannot both be Sikh and Westernized. Most Gurdwaras feed this apparent dissonance by offering children Punjabi classes, but no form of spiritual training, as though by merely learning to read and write in their mother tongue these children will grow to be fully realized Sikhs of the Guru.

5.2 Practice

A culture of deep meditation and service filled the early Sikh community. In this spiritual environment, saints were created, Gurbani was written, the Adi Granth was compiled, Miri Piri was founded, and Khalsa was born. Sikh culture was graced with simplicity and a lack of pretentious formality.

By comparison, rituals and readings are now the main occupation of the Granthis (priests), Paathis readers, and Ragis (musicians) in most Sikh temples. The rituals and conventions of present day Sikh culture take up several pages of instructions on the SGPC website. The culture of Gurdwaras today does not foster self-experience, self-empowerment or community development. In this presentation, we will call this trend the ‘brahminization’ of Sikh practice.

In recent times, it may be that the man who most truthfully shared the living, informal spirit of Guru Nanak was Siri Singh Sahib Harbhajan Singh Khalsa. In his thirty-six years of active teaching, he shared a consistent message that God is near at hand and accessible through meditation and good actions. Siri Singh Sahib also warned of the corrupting influence of ritualism. The following is a quote from a lecture.

Guru Nanak said, ‘I don’t want heaven. I don’t want hell. I don’t want imperial kingdom. And I don’t want to be a beggar. I don’t want anything. I just long to communicate with You through the Shabd (Word). You are my Shabd and I am your response.’

Look at that relationship! Sikh religion has to be understood – by Sikhs also. Sikh religion has become the biggest pivot of Brahmanism. It has lost its track. It has gone astray. Nothing is understood. (Siri Singh Sahib, June 6, 1989)

With the increasing wealth of the community, Gurdwaras continue to be built, bigger and more ostentatious, and readings continue to be commissioned. Seniors rule the holy places as presidents and committees with no thought for the next hundred years. Children and youth are bored with Gurdwara and seek their destiny elsewhere.

5.3 Culture

In its early centuries, the sublime awareness communicated by Gurbani was readily accessible because of the culture of meditation and service at the heart of the Sikh community. Practical role models and encouragement in the practice of meditation abounded for young and old.

Gurbani is today widely interpreted as theology and taught in the abstract. Translations usually centre around a distant, male God. The papers presented at a conference on Mool Mantra organized by the Department of Guru Nanak Studies at Guru Nanak Dev University in 1973, and subsequently published as Sikh Concept of the Divine illustrates this well. These papers do not address the personal realization of Mool Mantra, but contend only with conceptual and linguistic interpretations. The following depiction of Mool Mantra serves as an example of this thinking. In this paper, we will use the term ‘theologization’ to describe the transition from a culture of experience to one focused on theology.

There is but one God. True is His Name, creative His personality and immortal His form. He is without fear, sans enmity, unborn and self-illumined. By the Guru’s grace (He is obtained). (Manmohan Singh. 1962. translator, Siri Guru Granth Sahib (English & Punjabi translation), Volume 1, Amritsar: Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, 1)

Giving Gurbani, and especially the Mool Mantra, an abstract interpretation and treating it as though it were a matter understandable only by scholars, creates a divide between individual Sikhs and their Guru. If academics who should know better make Gurbani impersonal and hard to understand for adults, this is especially the case among young people who are usually mere afterthoughts in Gurdwara culture.

5.4 Self-concept

Originally, a Sikh of the Guru was defined by their soulful activities, specifically their meditation in the pre-dawn hours and throughout the day . The classical definition of a Sikh is given by Guru Ram Das:

One who considers themself a disciple of the True Guru should rise before the coming of daylight

And contemplate God’s Name. In the early hours of the morning, they should endeavour to bathe

In the ambrosial pool while repeating the Name taught by the Guru. In this way, they truly erase their sins.

Then, with the arrival of dawn, they should sing Gurbani and reflect on God’s Name all through the day.

One who with each breath and morsel remembers my God, God is a beloved disciple of the Guru. (Siri Guru Granth Sahib, 305-306)

Today, the terms ‘Punjabi’ and ‘Sikh’ and are often confused. Movements in both the US and UK are presently engaged in efforts to have Sikhs recognized as a distinct ethnic (not religious) group in future national censuses. Punjab is the birthplace of Guru Nanak, but a true Sikh is someone who practices a daily discipline and lives the lifestyle taught by the Guru. Eating, speaking and dressing Punjabi does not make one a Sikh. We will use the term ‘ethnicization’ here to describe attitudes and behaviours that support the reduction of the Sikh community from a spiritual movement to a cultural group.

5.5 Sovereignty

In its early days, the Sikh Panth conducted itself as a sovereign spiritual nation. This is no longer the case and may be attributed to two plausible causes: inherited psychological trauma and the brainwashing incurred when Sikhs lived under British rule.

Psychological trauma impacts self-esteem and the capacity for self-regulation, and can be transmitted through generations. Recovery from the accumulated trauma of 18th century holocausts, 19th century colonization, and the horrors of 1947 and 1984 may require many years of self-reflection and healing. Until this healing has occurred, unconscious trauma may play a role in the day to day life of the Panth.

Many Sikhs today take perverse pride in what may be termed ‘badges of bondage’ acquired during the period of British rule. Having finally inflicted defeat on the Sikh nation in 1849, the British were expert at rewarding their helpers with land, status and lucrative employment, and at destroying the lives of those who opposed them. Bhai Jawahar Singh, son of the legendary general of the Sikh Raj, Hari Singh Nalwa, had his lands taken away and was refused even a pension to live on, while the traitor Teja Singh was given a landed estate with a handsome income for the rest of his life. The Namdharis were the first to boycott British education, fashion, justice, and its postal service. Its leaders were made to suffer for their choices. The Akalis continued the effort for self-rule, but the British did their best to soften their opposition with perks and various kinds of corruption. Before long, they had many lassi-drinking Punjabis drinking tea, rolling their beards up into little nets, fighting their wars, and adopting English tastes and values. Today’s addiction to black tea, the habit of beard-tying or being ‘clean-shaven,’ reliance on Western justice, a preference for Western fashions, absorption in consumerism and uncritical acceptance of corporate culture go largely unchallenged in Sikh

culture, having long ago been abjectly absorbed and accepted into Sikh thinking.

5.6 Outreach

People say that Guru Nanak taught and travelled far and wide, reaching Mecca in the west, Tibet in the north, Assam in the east, and Sri Lanka to the south. The following Gurus also went on teaching tours to spread the faith.

While there are several Sikh missionary colleges in Punjab and Delhi today, their graduates are for internal consumption only, serving only existing Punjabi and Hindi speaking congregations. These colleges do not graduate true missionaries.

Such effective outreach as exists is independent of any religious body. Khalsa Aid, based in England, bravely provides vital supplies and disaster relief in Iraq, Mali, Greece, even flood-stricken England. Sikh yoga and meditation organizations originating in Siri Singh Sahib’s missionary efforts in the US also bring the Shabad Guru and aspects of Sikh lifestyle to dozens of countries on six continents. Both groups, however, are limited in their support from the larger Sikh community.

In the golden years of Sikh spirituality, the Sikh community was awake and alive to the real challenges of that time. The Guru and his followers opposed tyranny, bigotry, and ritualistic religion. They also meditated, worked honestly, and shared their earnings with the needy. Sikhs were known and appreciated for their courage and integrity. Today, the traditional prayer sarbat da bhalla – may the good of all be served – is more often understood as ‘may my good be served.’ This change in attitude naturally affects the reality of Sikh dharma. It also raises questions for Sikh youth finding their spiritual identity.

6. Restoring the Transmission of Meditative Awareness

The following is a proposed six-part prescription for restoring the transmission of meditative awareness:

6.1 From Secular Education to Spiritual Training

Create a global initiative to enlighten Sikh parents, educators, and community leaders about the spiritual potential and needs of young people. Develop a culture and create tools and opportunities to give children and youth meditation training, spiritual guidance, and suitable roles of community responsibility from an early age.

While the push to compete, capitalize and exploit remains undeniable, there is also a growing global trend toward holism, cooperation and the realization of psychosocial well-being. The best education in a world of increasing societal pressures, a deteriorating environment and declining planetary resources will likely be one that fosters resilience, adaptability and grace under pressure. The best students of this system, the masters of meditation, may well be the leaders of tomorrow.

6.2 From Brahmanism to Fostering Well-being

Train Granthis away from ritual readings and observances and instead toward fostering mental, physical, social and spiritual well-being in themselves and their congregations.

While there will certainly continue to be Sikhs who will like to pay a trained professional to do a prayer, sing a Shabad or do a reading for them, the training of Granthis and others in evidence-based healing arts and social work would likely enhance the quality of life in Sikh communities. Together with creating a cadre of culturally-sensitive wellness experts, this initiative might also increase the value and dignity of Granthis in the community.

6.3 From Theology to Science

Educate Sikhs and the general public on scientific findings supporting the positive relationship between meditation and well-being. Support research on the different types of Sikh meditation and their benefits. Up to the present, the majority of meditation studies have focussed on Buddhist and Hindu practices, while just a handful of researchers have looked at Sikh practices. Not only Sikhs, but the world may become richer should Sikh institutions in Amritsar and abroad develop policies supporting the science of Sikh meditation.

6.4 From Ethnic to Universal

Let all Sikh media emphasize the universal dimensions of Sikh teachings. Encourage, incentivize and arrange cross-cultural exchanges within and beyond the global Sikh community.

A global trend toward universal values and standards is on-going. This movement encompasses a tendency toward inclusion and against prejudice of all kinds. It includes an increasing view, unthinkable a generation ago, but very much a part of Guru Nanak's vision, that other species share with humans the capacity to feel, reason and communicate. In its purest expression, it may oppose stale religious conventions and embrace instead a simple love of all things living. One might speculate that with its life-affirming values and its regard for the unshorn human body as an extension of intrinsic being, Guru Nanak's way of life is a timely expression of the universal values of “biophilia,” the love of life.

6.5 From Colonial Thinking to Sovereign Mind

Celebrate and instil pride in original Sikh values and practices, while fostering education in global cultures, languages and religions. Encourage engagement and service in the wider community. The realization of true sovereignty begins with a life of self-discipline. According to psychologist M.E.P. Seligman, deficits in self-control often are related to depression, while exercises in self-mastery may increase self-confidence and resilience. Spiritual sovereignty involves a natural pride in one's own heritage, while retaining an appreciation of all things good and a disdain for things destructive and unhealthy, regardless of their origin.

6.6 Outreach

If Sikh individuals and institutions develop faith and confidence in themselves as purveyors of an empowering, science-based, deeply ecological, universal, service-based way of life, it may profoundly alter relationships within the Sikh community, while also changing the dynamic between Sikhs and the rest of the world. In the author’s view, a stressed, increasingly insular world desperately needs the sort of meditation and service inspired by Guru Nanak. Were Sikhs to begin to widely believe, practice and share the best of their tradition, it would certainly be a win-win for everyone.

7. A Case Study with Mool Mantra in Human Terms

While today’s predominant Sikh culture, at best, merely patronizes the spiritual experiences and potentialities of children and youth, the case study described here sets out to assess an eight-year-old Sikh child’s capacity to understand the core concepts underlying the Mool Mantra. In this case study we will use an interpretation of Siri Singh Sahib Harbhajan Singh Khalsa Yogi which depicts Mool Mantra as a template for self-realized being .

You are the One. Ek: One. Ong Kaar: You are the creation of the One. Sat Naam: Your identity is truth. Kartaa Purkh: You are the doer of everything. These are the faculties of God. Nirbhao, Nirvair–You are fearless and you are revengeless. Why? You are Akaal Moorat. That is because you are a personified God: Akaal Moorat. And when you reach that faculty of realization, then comes the other sentence: Ajoonee, Saibhang, Gur Prasaad. You are self-born because you are the product of the karma. Ajoonee: You didn’t come. You didn’t go. You are here. Here and now. You always talk about ‘here and now.’ Ajoonee means which does not come, which does not go. That is you. This identity is here. Soul came. Soul will go. Subtle body came. Subtle body will go. You won’t. Your identity is here now! Saibhang: by your own grace, by your own karma, by your own individuality, by your own essence, by your own consciousness, by your own corruption, by your own honesty, you are, you are! Nobody will tell you who you are. Nobody can tell you who you are. People can only help you. Therefore just remember in the end it said if you do not know all that, then you know by one virtue and that virtue is Gur Prasaad. Identify with the identity of the acknowledged learned. You will become learned. (Siri Singh Sahib, June, 1983)

The simplified version of Khalsa Yogi’s Mool Mantra interpretation used here is designed to fulfil the criteria of being:

1) accessible to the young

2) based on principles of well-being

3) science-based and experiential

4) universal (non-gendered, non-cultured)

5) sovereign (encouraging self-regulation)

Each phrase of Mool Mantra is given in the light of human experience with a reverse meaning, designed to help clarify the original meaning by contrast. These phrases, and their opposites, were illustrated by Japp Kaur over the course of a series of visits in early 2017, after a few classes of meditation instruction with the author. It should be noted that the artist required very little guidance in the execution of her work. Once the purport, simple meaning, and reverse meaning were explained to Japp, she set to work with alacrity and intuitive ease.

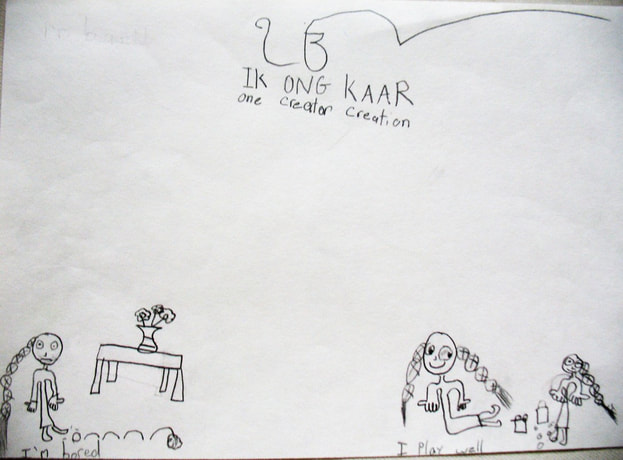

‘IK ONG KAAR’ (figure 1)

One Creator Creation

Basic translation: There is Oneness between Creator and Creation.

Purport: All the world is at play. May creativity, respect, and goodwill prevail.

Simple meaning: ‘I play well.’

Contrast: Creator and Creation are estranged.

Contrasting meaning: ‘I am bored.’

figure 1: ‘IK ONG KAAR’

In her depiction, Japp shows a clear difference between the girl at play with her companion and the solitary bored girl who appears frustrated.

In her depiction, Japp shows a clear difference between the girl at play with her companion and the solitary bored girl who appears frustrated.

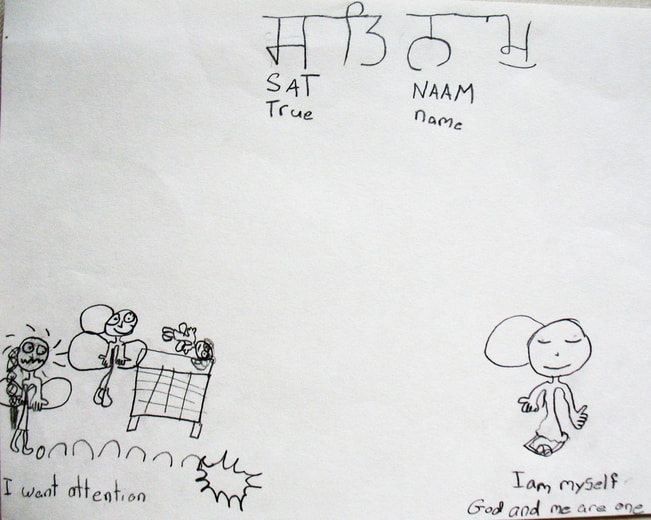

‘SAT NAAM’ (figure 2)

Intrinsic Identity

Translated as an affirmation: Be true to your Self.

Purport: May we be guided by our intrinsic values and meditation.

Simple meaning: ‘I am my Self. God and me are One.’

Contrast: I have no sense of myself or my value.

Contrasting meaning: ‘I want attention.’

figure 2: ‘SAT NAAM’

In this depiction, Japp shows the inner contentment and peace of the girl who has realized herself in contrast with her opposite who seems to be unsuccessfully competing for others’ attention.

In this depiction, Japp shows the inner contentment and peace of the girl who has realized herself in contrast with her opposite who seems to be unsuccessfully competing for others’ attention.

‘KARTA PURKH’ (figure 3)

Doing Being

Basic translation: Being is known through its actions.

Purport: May we seek out, and never shirk from, worthy actions.

Simple meaning: ‘I am not discouraged.’

Contrast: Being is discouraged and does not act.

Contrasting meaning: ‘There is no point in trying.’

figure 3: ‘KARTA PURKH’

Japp shows the resilience of the girl who has fallen from the jungle gym in comparison with the ‘loser’ who has given up trying.

Japp shows the resilience of the girl who has fallen from the jungle gym in comparison with the ‘loser’ who has given up trying.

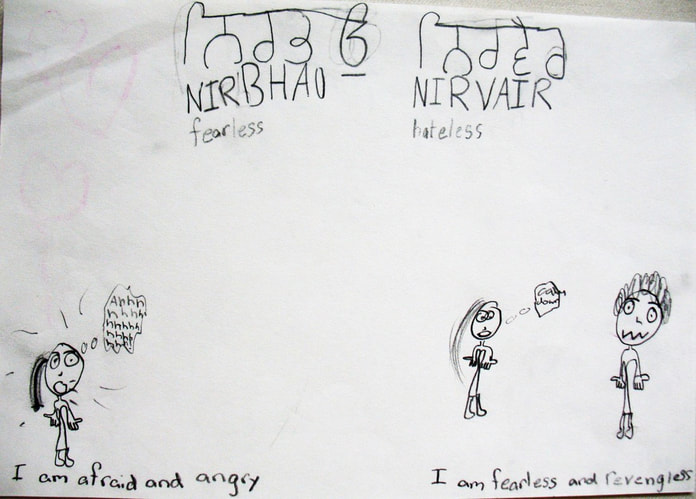

‘NIRBHAO NIRVAIR’ (figure 4)

Fearless Revengeless

Basic translation: Intrinsic being, realized through meditation, is fearless and revengeless.

Purport: Through meditation, may we live fearlessly and resist the impulse toward vengeance.

Simple meaning: ‘I am fearless and revengeless.’

Contrast: My mind is consumed by fear and vengeance.

Contrasting meaning: ‘I am afraid and angry.’

figure 4: ‘NIRBHAO NIRVAIR’

Japp’s Nirbhao-Nirvair girl tells herself to calm down in the face of provocation, while her opposite seems to be having an emotional meltdown.

Japp’s Nirbhao-Nirvair girl tells herself to calm down in the face of provocation, while her opposite seems to be having an emotional meltdown.

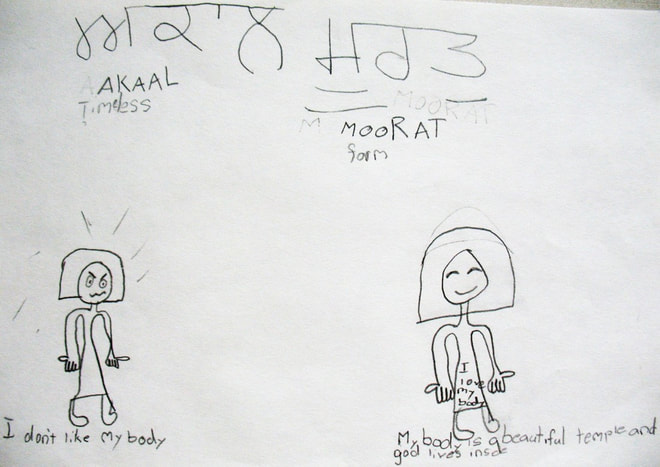

‘AKAAL MOORAT’ (figure 5)

Timeless Rendering

Basic translation: The human form is a perfect embodiment of timeless spirit.

Purport: That body is good which does good things.

Simple meaning: ‘My body is a beautiful temple and God lives inside.’

Contrast: Being is dissociated from embodiment.

Contrasting meaning: ‘I don't like my body.’

figure 5: ‘AKAAL MOORAT’

In this picture, Japp shows the role model smiling and blissful. She obviously loves her body and stands in stark contrast with the other girl whose contorted face expresses profound frustration and malaise.

In this picture, Japp shows the role model smiling and blissful. She obviously loves her body and stands in stark contrast with the other girl whose contorted face expresses profound frustration and malaise.

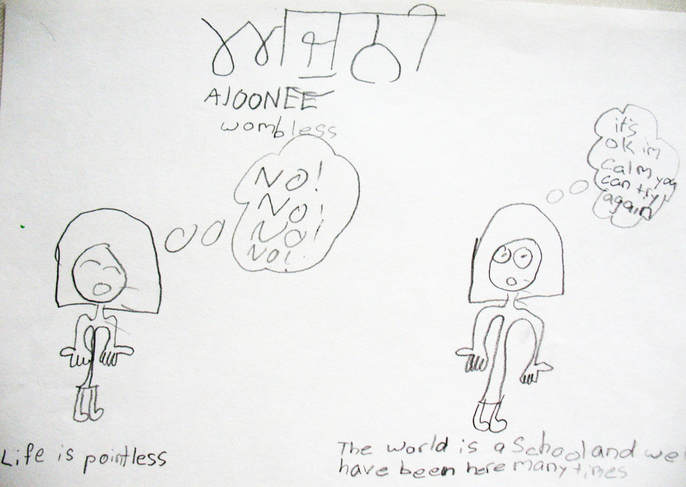

‘AJOONEE’ (figure 6)

Wombless

Basic translation: Being is independent of any specific incarnation.

Purport: May we fulfill the purpose of this life this one time.

Simple meaning: ‘The world is a school and we have been here many times.’

Contrast: Being is attached to this body and this lifetime only.

Contrasting meaning: ‘Life is pointless.’

figure 6: ‘AJOONEE’

Japp’s wise girl in this picture appears to be facing a challenge by calming herself and encouraging herself to try again, while the unwise girl sees no point and is immersed in heated frustration and denial.

Japp’s wise girl in this picture appears to be facing a challenge by calming herself and encouraging herself to try again, while the unwise girl sees no point and is immersed in heated frustration and denial.

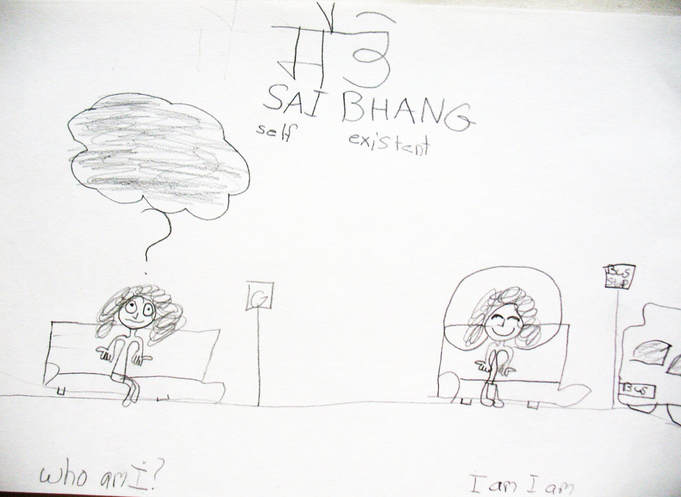

‘SAIBHANG’ (figure 7)

Self-existent

Basic translation: Existing in and of, and ultimately for, oneself

Purport: May we experience the blessing of being happy with ourselves.

Simple meaning: ‘I am, I am.’

Contrast: Existing primarily for the gratification of others.

Simple meaning: ‘Who am I?’

figure 7: ‘SAIBHANG’

In this picture, Japp’s happy girl is immersed in spiritual bliss. It is not clear whether the bus is just arriving or has just left the stop, but she seems perfectly attuned to the situation, while her unhappy girl ruminates under a dark cloud.

In this picture, Japp’s happy girl is immersed in spiritual bliss. It is not clear whether the bus is just arriving or has just left the stop, but she seems perfectly attuned to the situation, while her unhappy girl ruminates under a dark cloud.

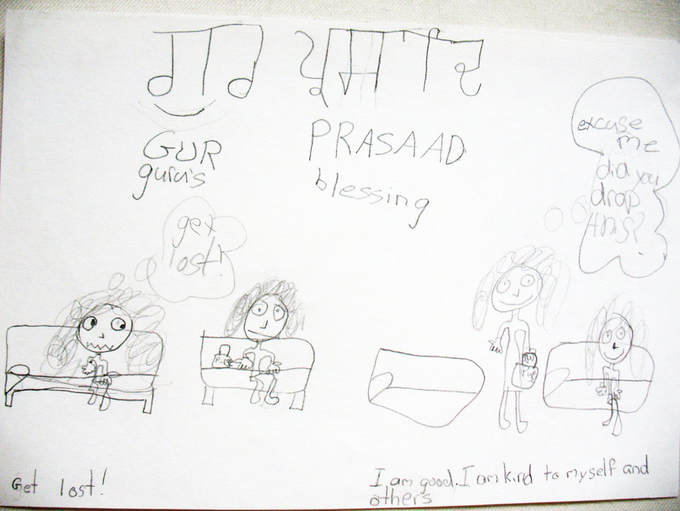

‘GUR PRASAAD’ (figure 8)

Guru’s Grace

Basic translation: Intrinsic being is realized by the Guru's grace. It is inherently graceful.

Purport: The more realized we are, the sweeter we become.

Simple meaning: ‘I am good. I am kind to myself and others.’

Contrast: Life without wisdom and without grace.

Simple expression: ‘Get lost!’

figure 8: ‘GUR PRASAAD’

In ‘Gur Prasaad,’ Japp shows her role model being a blessing to others by retrieving another girl’s lost purse. Her opposite is utterly annoyed and wishes her neighbour to ‘get lost.’

In ‘Gur Prasaad,’ Japp shows her role model being a blessing to others by retrieving another girl’s lost purse. Her opposite is utterly annoyed and wishes her neighbour to ‘get lost.’

In this case study we are able to see a simple case of transmission of spiritual awareness from a Sikh adult practiced in meditation to a young Sikh child with a beginning practice of meditation. We can observe that the young artist seems to have understood the core values of the Mool Mantra set in a human context and to have presented each of its constituent ideas with creativity and artistry appropriate to her age. Further studies of children, some with and some without meditative experience, may deepen our understanding of this original case study.

8. Conclusion

In this series of articles, we have discussed the important role of meditation in early Sikh history. We have appreciated the evocative depiction of a geography of meditative experience using a rich pallet of conceptual, locational, physiological and subjective terminologies. We have studied Gurbani and historical accounts of the passing of the Guru’s meditative awareness to his foremost disciples. We have also taken note of Guru Gobind Singh’s warning against leaving his distinctive path and taking up a path of rituals. We have examined Sikh history and found there the first hints of the breaking of this chain of transmission in the mid 1700’s when sheer survival from persecution and war were primary concerns. In the time of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, we observed the declining status of women and the rise of rituals in the imperial court and throughout Sikh society. We have also looked at the period of British colonial rule over the Sikhs, when many British habits and forms of thinking became predominant, never to recede even with the achievement of India’s political independence.

Suggestions have been made to recover the vital transmission of meditative awareness from Guru to Sikh. These suggestions involve a refocussing of energies toward: spiritual training of children and youth, fostering individual and community well-being, research and education on the benefits of Sikh meditation, developing a culture of Sikh pride, and thoughtful outreach to other communities.

Sikh children and youth present a case of special concern. Innocent and unknowledgeable about Sikh teachings and traditions, they are utterly dependent on parents and elders for their guidance and support. As our case study has shown, a modern Sikh child as young as eight years old is capable of grasping and working with core Sikh concepts if they are presented to them in simple language and in human terms. The legacies of Guru Harkrishan, Bibi Nanaki, Baba Budha, Baba Fateh Singh and Baba Zorowar Singh bear witness that children can reach to high levels of spiritual realization if only they are properly instructed.

Children are children. They are innocent, but they are not stupid. They do not naturally crave digital entertainments. Insensitivity and addictive behaviours are first modelled by elders who in their pursuit of worldly objectives may ignore the reality of the precious, God-given souls at their feet.

Adults are uniquely situated to guide the fortunes of the young. Through their teaching and example, they may guide their children toward egotistical achievements of wealth, power and status and the stresses and calamities that go along with them. With wisdom, they may guide them instead to a life of contemplation and service of others.

Much is made of the supposed status of women in Sikh dharma, equal to men in all things. This work shows a dramatic drop in the role and prestige of womankind during the reign of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, a decline from which Sikh women arguably have never recovered. With the decline in women’s position in Sikh society, there is also a virtual disappearance of women and children in meaningful roles in Sikh dharma which continues to this day.

Sikh dharma has behind it a glorious history of empowerment and social transformation. It carries with it also generations of physical and psychological trauma. It may be that some Sikhs today are too haunted by the ghosts and demons of the near and distant past – the genocidal Mir Mannu, the traitor Lal Singh, the mass murderer, General Dyer; the Partitionist, Muhammad Jinnah; the cunning Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi – to take their rightful place in the present.

The interruption of the unbroken transmission of the Guru’s meditative awareness may be part cause and part consequence of these harrowing turns of history. It is the author’s hope that a renewed and invigorated transmission of that inspired state of mind may take the Sikh nation from the depths of despair and disunity to a return to the heights of dedicated service and love of humanity.

It is hoped that the suggestions made here will be discussed and improved upon by those with an interest in them. Assuming the suggestions are more or less valid, a larger question arises: Who will implement them? Will souls at the apex of the foremost religious organization of Sikh dharma, the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee in Amritsar recognize a need for change and take the lead? Is there a possibility of grassroots education and mobilization? What are the chances of everyone working together to this end?

Time will tell.

In this series of articles, we have discussed the important role of meditation in early Sikh history. We have appreciated the evocative depiction of a geography of meditative experience using a rich pallet of conceptual, locational, physiological and subjective terminologies. We have studied Gurbani and historical accounts of the passing of the Guru’s meditative awareness to his foremost disciples. We have also taken note of Guru Gobind Singh’s warning against leaving his distinctive path and taking up a path of rituals. We have examined Sikh history and found there the first hints of the breaking of this chain of transmission in the mid 1700’s when sheer survival from persecution and war were primary concerns. In the time of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, we observed the declining status of women and the rise of rituals in the imperial court and throughout Sikh society. We have also looked at the period of British colonial rule over the Sikhs, when many British habits and forms of thinking became predominant, never to recede even with the achievement of India’s political independence.

Suggestions have been made to recover the vital transmission of meditative awareness from Guru to Sikh. These suggestions involve a refocussing of energies toward: spiritual training of children and youth, fostering individual and community well-being, research and education on the benefits of Sikh meditation, developing a culture of Sikh pride, and thoughtful outreach to other communities.

Sikh children and youth present a case of special concern. Innocent and unknowledgeable about Sikh teachings and traditions, they are utterly dependent on parents and elders for their guidance and support. As our case study has shown, a modern Sikh child as young as eight years old is capable of grasping and working with core Sikh concepts if they are presented to them in simple language and in human terms. The legacies of Guru Harkrishan, Bibi Nanaki, Baba Budha, Baba Fateh Singh and Baba Zorowar Singh bear witness that children can reach to high levels of spiritual realization if only they are properly instructed.

Children are children. They are innocent, but they are not stupid. They do not naturally crave digital entertainments. Insensitivity and addictive behaviours are first modelled by elders who in their pursuit of worldly objectives may ignore the reality of the precious, God-given souls at their feet.

Adults are uniquely situated to guide the fortunes of the young. Through their teaching and example, they may guide their children toward egotistical achievements of wealth, power and status and the stresses and calamities that go along with them. With wisdom, they may guide them instead to a life of contemplation and service of others.

Much is made of the supposed status of women in Sikh dharma, equal to men in all things. This work shows a dramatic drop in the role and prestige of womankind during the reign of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, a decline from which Sikh women arguably have never recovered. With the decline in women’s position in Sikh society, there is also a virtual disappearance of women and children in meaningful roles in Sikh dharma which continues to this day.

Sikh dharma has behind it a glorious history of empowerment and social transformation. It carries with it also generations of physical and psychological trauma. It may be that some Sikhs today are too haunted by the ghosts and demons of the near and distant past – the genocidal Mir Mannu, the traitor Lal Singh, the mass murderer, General Dyer; the Partitionist, Muhammad Jinnah; the cunning Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi – to take their rightful place in the present.

The interruption of the unbroken transmission of the Guru’s meditative awareness may be part cause and part consequence of these harrowing turns of history. It is the author’s hope that a renewed and invigorated transmission of that inspired state of mind may take the Sikh nation from the depths of despair and disunity to a return to the heights of dedicated service and love of humanity.

It is hoped that the suggestions made here will be discussed and improved upon by those with an interest in them. Assuming the suggestions are more or less valid, a larger question arises: Who will implement them? Will souls at the apex of the foremost religious organization of Sikh dharma, the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee in Amritsar recognize a need for change and take the lead? Is there a possibility of grassroots education and mobilization? What are the chances of everyone working together to this end?

Time will tell.

References

Alexander, F. 1931. Buddhistic Training as an Artificial Catatonia (The Biological Meaning of Psychic Occurrences). Psychoanalytic Revue, 18(2):129-145.

Anand, Balwant Singh. 1996. Guru Har Krishan. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 2:254-256.

Ashok, Shamsher Singh. 1996. Mata Jito. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 2:385.

Ashok, Shamsher Singh. 1997. Panj Piare. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 3:282-284.

Ashok, Shamsher Singh. 1998. Sahib Devan. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 4:16-17.

Ashok, Shamsher Singh. 1998. Mata Sundari. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 4:277-278.

Ashok, Shamsher Singh. 1998. Zorowar Singh. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 4:461.

Bailey, Kenneth D. 1994. Sociology and The New Systems Theory: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1994.

Banerjee, A. C. 1998. Guru Tegh Bahadur. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 4:329-334.

Brefcynski-Lewis, J. A., A. Lutz, H. S. Schaefer, D. B. Levinson, and R. J. Davidson. 2007. Neural correlates of attentional expertise in long-term meditation practitioners. National Academy of the Sciences. 104(27), 11483-11488.

Dawe, Donald G. 1997. Guru Nanak. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 3:165-183.

Dekel, Rachel & Goldblatt, Hadass. 2008. Is There Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma? The Case of Combat Veterans' Children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 78(3) 281-289.

Dhaliwal, Tanbir. April 8, 2017. Every 8th Punjabi suffering from mental illness: NMH Survey 2016-2017. Hindustan Times http://www.hindustantimes.com/punjab/every-8th-punjabi-suffering-from-mental-illness-national-mental-health-survey-2016-2017/story-dZPldSU2FAFuvHEMNDOPRP.html.

Dilgeer, Harjinder Singh. 1980. The Akal Takht. Jullundur. Punjabi Book Company.

Esch, Tobias. 2013. The Neurobiology of Meditation and Mindfulness. In Schmidt, S., Walach, H. (eds.) Meditation – Neuroscientific Approaches and Philosophical Implications. Studies in Neuroscience, Consciousness and Spirituality, Vol. 2. Springer, Cham, 153-173.

Fox, Kieran C. R., Savannah Nijeboer, Matthew L. Dixon, James L. Floman, Melissa Ellamil, Samuel P. Rumak, Peter Sedimeier and Kalina Christoff. 2014. Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 43, June 2014, 48-73.

Gandhi, Surjeet Singh. 2004. A Historian’s Approach to Guru Gobind Singh. Amritsar: Singh Brothers.

Gatto, John Taylor. 2017. Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling. Gabriola Island, Canada: New Society Publishers.

Goyal, Madhav, Sonal Singh, Erica M. S. Sibinga, Neda F. Gould, Anastasia Rowland-Seymour, Ritu Sharma, Zackary Berger, et al. 2014. Meditation Programs for Psychological Stress and Well-being: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine (174)3, 357-368.

Grewal, J. S. 1990. The Sikhs of the Punjab. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gupta, Hari Ram. 1973. History of Sikh Gurus. New Delhi: U. C. Kapur and Sons.

Hall, Kathleen. 1995. ‘There’s a Time to Act English and a Time to Act Indian’: The Politics of Identity Among British-Sikh Teenagers. In Children and the Politics of Culture. Sharon Stephens, ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 243-264.

Jakara. 2017. Do You Want a ‘Sikh’ Category? www.jakara.org/census2020.

Jakobsh, Doris R. 2003. Relocating Gender in Sikh History: Transformation, Meaning and Identity. New York: Oxford University Press.

Jolly, Surjit Kaur. 1988. Sikh Revivalist Movements: The Nirankari and Namdhari Movements in Punjab in the Nineteenth Century (A Socio-Religious Study). New Delhi: Gitanjali Publishing House.

Kapany, Narinder Singh Kapany. 2017. ‘Message from the Chair,’ published in the program for the 50th Annual gala program of the foundation, May 5-7, 2017 http://sikhfoundation.org/50years/wp-content/uploads/Sikh-Foundation-50-Years-Program-of-Events-reduced.pdf

Khalsa Aid. 2017. www.khalsaaid.org

Khalsa, Guru Fatha Singh. 1996. Badges of Bondage: The Conquest of the Sikh Mind, 1847-1947 C.E. Toronto: Self-published.

Khalsa, Guru Fatha Singh. 2008. The Essential Gursikh Yogi: The Yoga and Yogis in the Past, Present and Future of Sikh Dharma. Toronto: Self-published.

Khalsa, Guru Fatha Singh. 2017. O Canada! Our Canada. www.sikhnet.com/news/o-canada-our-canada.

Khalsa, Guru Fatha Singh. January 2001. Wanted: More & Better Missionary Colleges (Originally titled: The Shame of the Missionary Colleges). The Sikh Review (49)1, 35-39.

Khalsa, Livtar Singh. 1976. Stand as the Khalsa. Sikh Dharma Brotherhood (2)3, 8-9.

Latif, Syad Muhammad. 1964. History of the Panjab: From the Remotest Antiquity to the Present Time. New Delhi: Eurasia Publishing House.

Lev-Wiesel, Rachel. 2007. Intergenerational transmission of trauma across three generations: A preliminary study. Qualitative Social Work. (6)1: 75-94.

Lewis, David. 2010. Nongovernmental Organizations, Definition and History. 10.1007/978-0-387-93996-4_3.

Loehlin, C. H., and Rattan Singh Jaggi. 1995. Dasam Granth. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 4:514-531.

Lutz, Antoine, Lawrence L. Greschar, Nancy B. Rawlings, Matthieu Ricard, and Richard J. Davidson. 2004.

Long-term meditators self-induce high-amplitude gamma synchrony during mental practice. National Academy of the Sciences (101)46, 16369-16373.

MacAuliffe, Max Arthur. 1978. The Sikh Religion: Its Gurus, Sacred Writings and Authors, 6 Volumes. New Delhi: S. Chand and Company (Originally published in 1909).

Mann, Gurinder Singh. 2000. Sikhism in the United States of America. In The South Asian Religious Diaspora in Britain, Canada, and the United States. Albany: State University of New York Press, 259-276.

Mansukhani, G. S. 1997. Guru Ram Das. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 3:450-454.

McLeod, W. H. 1998. Shabad. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 4:88-90.

McLeod, W. H. 2003. Sikhs of the Khalsa: A History of the Khalsa Rahit. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Meredith, J. L. 1980. Meredith’s Big Book of Bible Lists. New York: Inspirational Press.

Miller, W. R., and Thorensen, C. E. 2003. Spirituality, religion, and health: An emerging field. American Psychologist, 58(1), 24-35.

Miri Piri Academy. 2017. www.miripiriacademy.com

Monro, Robin, A. K. Ghosh, and Daniel Kalish. 1989. Yoga Research Bibliography. Cambridge: Yoga Biomedical Trust.

Nabha, Bhai Kahan Singh. 1981. Gurushabad Ratanaakar Mahaan Kosh, 4th edition. Patiala: Bhaashaa Vibhaag Punjaab.

Nayar, Kamala Elizabeth. 2004. The Sikh Diaspora in Vancouver: Three Generations and Tradition, Modernity, and Multiculturalism. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Newberg, A. B., and J. Iverson. 2004. The neural basis of the complex task of meditation: Neurotransmitter and neurochemical considerations. Medical Hypotheses 61(2), 282-291.

Oberoi, Harjot. 1994. The Construction of Religious Boundaries: Culture, Identity, and Diversity in Sikh Tradition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Olivelle, Patrick. 1998. The Early Upanishads: Annotated Text and Translation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ospina, Maria B., Kenneth Bond, Mohammad Karkhaneh, Nina Buscemi, Donna Dryden, Vernon Barnes, Linda E. Carlson, Jeffery A. Dusek, David Shannahoff-Khalsa. 2008. Clinical Trials of Meditation Practices in Health Care: Characteristics and Quality. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 14(10), 1199-1213.

Padam, Piara Singh. 1995. Guru Amar Das. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism, 2nd edition. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 1:87-89.

Puff, Robert (July 7, 2013) An Overview of Meditation: Its Origins and Traditions. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/meditation-modern-life/201307/overview-meditation-its-origins-and-traditions.

Rajguru, G. N. 1995. Baba Buddha. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism, 2nd edition. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 1:399-400.

Salmon, Catherine, and Todd K. Shackelford. (eds.) 2011. The Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Family Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Schwartz, Astrid, and Kurt Jax (eds.) 2011. Ecology Revisited: Reflecting on Concepts, Advancing Science. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Seligman, M. E. P. 1998. The prediction and prevention of depression. In The Science of Clinical Psychology: Accomplishments and Future Direction. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 201-214.

Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC). 2017. Rehat Maryada (Code of Conduct) in English. http://sgpc.net/sikh-rehat-maryada-in-english/

Sikh Dharma International. 2017. www.sikhdharma.org

Singh, Bhagat. 1990. Maharaja Ranjit Singh and His Times. New Delhi: Sehgal Publishers Service.

Singh, Bhagat. 1996. Guru Har Rai. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 2:261-263.

Singh, Fauja. 1979. Guru Amar Das: Life and Teachings. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers.

Singh, Fauja. 1996. Guru Hargobind. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 2:232-235.

Singh, Fauja. 1997. Panth. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 3:288-289.

Singh, Ganda. 1996. Guru Gobind Singh. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 2:88-92.

Singh, Gopal. 1988. A History of the Sikh People (1469-1988) (2nd ed.). New Delhi: World Book Centre.

Singh, Gurharpal, and Darshan Singh Tatla. 2006. Sikhs in Britain: The Making of a Community. London: Zed Books.

Singh, Gurnek. 1995. Baba Atal Rai. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism, 2nd edition. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 1:208.

Singh, Harbans. 1994. The Heritage of the Sikhs (revised ed.). New Delhi: Manohar.

Singh, Harnam. 1995. Bibi Bhani. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism, 2nd edition. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 1:346.

Singh, Kharak. 2009. Turn of the Century: Sikh Concerns and Responses. Amritsar: Singh Brothers.

Singh, Khushwant. 2004. A History of the Sikhs, Volume 2, 2nd edition. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Singh, Major Gurmukh. 1996. Baba Gurditta. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 2:144-145.

Singh, Major Gurmukh. 1996. Jetha Bhai. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 2:374.

Singh, Manmohan Singh. 1962. translator, Siri Guru Granth Sahib (English and Punjabi translation), Volume 1, Amritsar: Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee.

Singh, Nikki-Guninder Kaur. 2011. Sikhism: An Introduction. New York: I. B. Taurus and Company.

Singh, Patwant Singh, and Jyoti M. Rai. 2008. Empire of the Sikhs: The Life and Times of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. London: Peter Owen Publishers.

Singh, Pritam. 2002. editor, Sikh Concept of the Divine (2nd ed.). Amritsar: Guru Nanak Dev University Press.

Singh, Satbir. 1989. Jis Dithay Sabh Dukh Jaa-ay: Sachitar Jeevnee Guroo Har Krishan Jee (Punjabi), Jullundar: New Book Company.

Singh, Taran. 1996. Bhai Kaliana. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 2:416-417.

Singh, Taran. 1998. Sri Guru Granth Sahib. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 4:239-252.

Singh, Tarlochan. 1981. Life of Guru Har Krishan. Delhi: Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee.

Solberg, Eric, E., Are Holen, Olvind Ekeberg, Bjarne Osterund, Ragnhild Halvorsen, and Leiv Sandvik. 2004. The effects of long meditation on plasma melatonin and blood serotonin. Medical Science Monitor, 10(3): CR96-101.

The Sikh Network. 2016. UK Sikh Survey 2016 Findings. thesikhnetwork.com/uk-sikh-survey-2016-findings/.

Solomon, Robert C. 1992. Ethics and Excellence: Cooperation and Integrity in Business. New York: Oxford University Press.

Talib, Gurbachan Singh. 1995. Guru Arjan Dev. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 1:188-193.

3HO Foundation. 1973. Teachers’ Kit. Los Angeles: 3HO Foundation.

3HO Foundation. 2017. www.3ho.org.

Vivekananda, Swami. 1973. Raja Yoga. New York: Ramakrishna Vedanta Center.

Williamson, Lola. 2010. Transcendent in America: Hindu-Inspired Meditation Movements as New Religion. New York: New York University Press.

Wilson, Edward, O. 1983. Biophilia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wohlleben, Peter. 2016. The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate: Discoveries from a Secret World. Vancouver/Berkeley: Greystone Books.

Alexander, F. 1931. Buddhistic Training as an Artificial Catatonia (The Biological Meaning of Psychic Occurrences). Psychoanalytic Revue, 18(2):129-145.

Anand, Balwant Singh. 1996. Guru Har Krishan. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 2:254-256.

Ashok, Shamsher Singh. 1996. Mata Jito. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 2:385.

Ashok, Shamsher Singh. 1997. Panj Piare. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 3:282-284.

Ashok, Shamsher Singh. 1998. Sahib Devan. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 4:16-17.

Ashok, Shamsher Singh. 1998. Mata Sundari. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 4:277-278.

Ashok, Shamsher Singh. 1998. Zorowar Singh. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 4:461.

Bailey, Kenneth D. 1994. Sociology and The New Systems Theory: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1994.

Banerjee, A. C. 1998. Guru Tegh Bahadur. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 4:329-334.

Brefcynski-Lewis, J. A., A. Lutz, H. S. Schaefer, D. B. Levinson, and R. J. Davidson. 2007. Neural correlates of attentional expertise in long-term meditation practitioners. National Academy of the Sciences. 104(27), 11483-11488.

Dawe, Donald G. 1997. Guru Nanak. In Singh, Harbans (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University Press, 3:165-183.

Dekel, Rachel & Goldblatt, Hadass. 2008. Is There Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma? The Case of Combat Veterans' Children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 78(3) 281-289.

Dhaliwal, Tanbir. April 8, 2017. Every 8th Punjabi suffering from mental illness: NMH Survey 2016-2017. Hindustan Times http://www.hindustantimes.com/punjab/every-8th-punjabi-suffering-from-mental-illness-national-mental-health-survey-2016-2017/story-dZPldSU2FAFuvHEMNDOPRP.html.

Dilgeer, Harjinder Singh. 1980. The Akal Takht. Jullundur. Punjabi Book Company.

Esch, Tobias. 2013. The Neurobiology of Meditation and Mindfulness. In Schmidt, S., Walach, H. (eds.) Meditation – Neuroscientific Approaches and Philosophical Implications. Studies in Neuroscience, Consciousness and Spirituality, Vol. 2. Springer, Cham, 153-173.