Home

Changing Perspectives On The Place There's No Place Like

There's no place like home. Though they may differ in appearance and what they are made of, everyone agrees that there is no place like home.

World-wide, a home may mean a yurt or a bungalow, a tent or an apartment, a houseboat or a thatched hut, an adobe house or a cave, a lean-to or a hospital room, a prison cell or a tree house. People live in structures that are permanent or temporary, mobile or stationary, and made of a vast array of natural and synthetic materials.

Inside the home, again, there is great diversity. The foods, of course are different, as are the languages spoken and the people themselves. Some homes are “home” to large, extended families with three or four generations, grandparents, great grandparents, children, great grandchildren, mothers and fathers, all together under one roof. In some homes there is only one person and a cat. Some are joint households shared by one or more brothers, their parents, wives and children. Some places are home to just one person and a caregiver. In some homes there are a husband and several wives with their children. Some homes have same-sex partners, some with children. Some homes have several dogs and cats. In some, a water buffalo may come inside for the night. Home can take many, many forms.

All around the world, homes are a necessity of life. When a child is born to its mother, they both need a safe place to bond while the infant grows and the mother recovers her strength. If the mother is lucky, there will be helping hands at home to assist in her chores and caring for her child. A good home provides security, companionship, food, and comfort for the body, mind and spirit to everyone who lives there.

Many people live in an ancestral home, a house that has been passed down to them from generation to generation. Many people live in the village or town where their ancestors lived before them for hundreds of years. Those who live in a nomadic culture may consider the whole region they inhabit as their home. For thousands of years, people have tended to be rooted in their traditional homes, be they a village or a town or a whole region.

Occasionally, a great migration takes place where circumstances force people to abandon their ancestral home. People can be threatened by natural or human forces – drought or flood or war or some other social upheaval. Migrations are always stressful to family life. The journey to a new home can be dangerous. Important social networks and support systems can be lost. The people can find themselves unwelcome in their new homeland. It can at first be difficult to find food and shelter there.

The past centuries, beginning in England, have been marked by a constant flow of people from their homes in the country to new homes in the urban manufacturing and trading centres of the world. Seeking a more prosperous life and greater freedom, tens and hundreds of millions of people have migrated from the familiarity of their traditional home on the farm to the uncertainty of life in the largely impersonal city.

Advances in industry, commerce, and communication, and the development of powerful military states, called for the creation of mass education which also changed the nature of the household. Now, instead of children staying at home and learning their family profession, they ventured out, five or six days a week to schools which taught them subjects and values often unknown to their elders.

In the course of the industrial age, homes have changed substantively. Where once a home was itself made by the family that lived there with the help of their community, and filled with familiar goods all made by people known to the family, today both the structure and its contents are likely mass-produced. Where once family activities were centred around the work cycle of the farm or family business and punctuated by meals and worship, many modern families share few interests, eat out, and do not participate in organized religion. Whereas elders used to be the valued guardians of family lore and wisdom, in the new arrangement, elders are considered a burden and shunted aside, often to a “home” for older people. Many young people, taken up by a commercial culture that celebrates youth and freedom, heed the siren call of individualism and leave their homes to live alone while finishing their education or taking up a job.

Regardless of all these changes, the appeal of having a home, a place where you belong, even in a culture as highly individualistic as ours is such that mere houses are marketed as real estate and sold as “homes.” There is also a growing popular interest in tracing family roots through past generations, known as genealogy. This is the sociological view of home, across cultures and across history.

If we think back, our concept of home has deeper roots than we might readily imagine. Our first home, after all, where we lived for nine months or so, was a cozy little place inside our mothers' bellies. Food and shelter and companionship were provided. There were no bills to pay, no taxes, and nothing to go out and get. Everything we needed was right there.

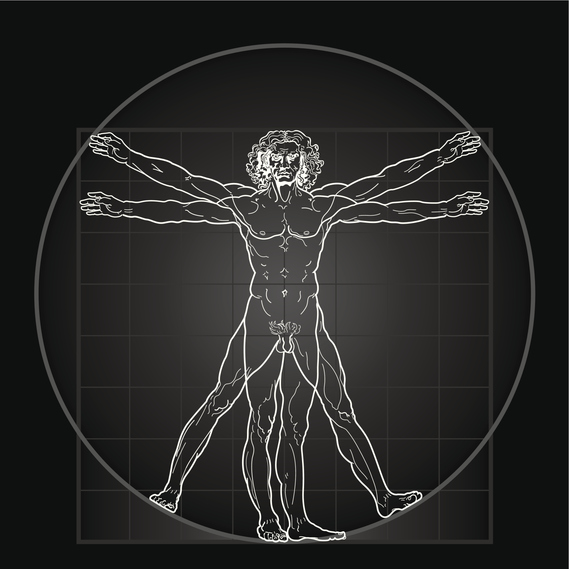

So it was until we moved on from that place to a new home of family and culture, the sociological home described earlier. Our discharge from our mother's womb and presentation to the world also occasioned a slow realization of our own body as the home of our mind and spirit.

Made of flesh and blood and bone and white matter and grey matter and a good deal else, our new home visibly took up space and time. It needed cleaning and nurture and occasional rest. And, day by day, it grew and grew as our abilities also evolved.

This home had nine points of entry and exit, and the capacity for engaging the world around us in multiple ways. After a couple of years, it became imminently mobile. It also gave us the ability to communicate with others. Within it as well was the capacity, upon maturation, to carry life forward and, if we happened to have the body of a woman, a uterus to serve as a temporary home for newcomers to our world just as our mother's womb had been a home to us.

The greatest delight and fulfillment of life is in reaching out to others, young and old, strangers and familiar, helping them to feel welcome and at peace and at home in the tumult of the world. It is in reaching out to the displaced and the lonely, the wounded and the abandoned, those the world has rejected as unattractive or unwholesome, people of all different constitutions, understandings, and habits, in the hope of joining with them in an active bond of thankful and respectful humanity, that we ourselves find peace.

It is difficult work. To be truly effective, we need to sink powerful foundations into the physical platform of our bodies. We need to turn on the lights, check the plumbing, and be sure the power is flowing on all the floors. We need to become familiar with the subtle substrate of power residing in the mind and breath and learn to use them to the best advantage of ourselves and others.

Starting at the base of humility, we discover a world of retention and release, security and insecurity. Our foundation located at the anus determines how earthy we are, how much our thinkings are grounded in reality, the degree to which we harbour resentment and the extent to which we are willing to forgive and let go. This is our centre of “spiritual potty training” and, coming to terms with it creatively, it becomes for us a humble first among heavens.

On the second floor, we find the dynamics of relationship, the fluidity of change, the ice of rigidity, and the fog of indecision. Itself the locus of life and the transmission of life, this is the centre of our ability or inability to trust and be trusted, and to be engaged or disengaged in any sort of relationship. When the lights are on and the power connected here, we become responsible partners in all endeavours.

The third level is the fiery kingdom of the navel. This is the centre of our strength and weakness, stability and instability. When we are “at home” in the navel, we are physically, mentally and spiritually robust. When we are not, our incapacity is endless. This is the centre of deep and abiding spirit, the breath. In martial arts, it is called the “chi centre.” When it is strong, it is our third heaven and key to the heart. No one presides in the kingdom of the heart without first experiencing the irresistible force of the universe that lives in, and flows through, them.

The fourth floor is the heart centre, realm of caring and apathy. Without being ignited by the holy fire of the third centre, initiated by the sacred waters of the second, and grounded by the reality of the first, the capacity to deeply care for oneself or others exists hardly at all. When galvanized by the purifying power of the third centre however, our capacity for caring turns endless. We may care for people and things, large and small, grand and humble. This is the sacred heart, fourth in the hierarchy of spiritual attainment, the centre of caring and sharing.

Fifth is the throat centre. At the fifth lives the sad silence of the speechless, the unspoken, and the dumb. But at the locus of communication, even the deaf can find the means to make themselves understood. Where the compassion and caring of the heart flows strongly, these sentiments are made lyrical at the fifth centre where they are readily translated into poetry and song, melody and dance, for all to see and hear and understand.

Ranked above the centre of communication is the sixth centre, the “third eye.” When there is no life in the lower centres, this eye is blind. It sees nothing. But when inspired by the light of pure consciousness, it is the locus of foresight, insight and circumspection, the home of thoughtful and gracious living. It is the sixth, and therefore the next to ultimate, heaven for a human being.

Elevated above all the other centres with their dynamics of forgiveness and trust, empowerment and empathy, communication and insight, is the seventh. Deemed “seventh heaven,” it is the place of faith, inner communion, and surrender to the greatest good. The seventh centre is the final abode of fearlessness and sacrifice. Those who have passed the tests of the other centres, live here in profound humility and thanks. This is the place of peace beyond understanding.

A rare person summons together the powers of the seven centres. Their being radiates purity and grace, courage and kindness, strength and humility. They bring this energy to bear on any situation, even without speaking.

An elevated being is not always recognized, not always respected, but they dedicate their all to helping the suffering and the poor, the lost and the hopeless, in any way they can. People of earthly authority and power often oppose them, spreading slander, doubt and all kinds of adversity. The person of elevation and faith stands firm and fearless in the face of tests and opposition.

Unlike most people, the saint knows full well that their days, their hours, their breaths here are numbered. And while there is merit in helping the distraught and disadvantaged to feel at peace and at home in this world, they realize also that this world is but a transitory place, a mountain of smoke.

Being firmly grounded and established in their body, mind, and spirit, the enlightened sage remembers that good actions pave the way to peace, but there is no place like the ultimate abode of peace beyond this life. They remember that just as long ago they were discharged from the temporary shelter of their mother's womb, even so, they will also one day exit their physical shell and leave all that is familiar to them to make, at last, their final journey home.