A Story About Racism

| a_story_about_racism.pdf | |

| File Size: | 207 kb |

| File Type: | |

Let me tell you a story about racism, a personal story of mine. I was born in Canada, the first child of German immigrants. German was the first language I learned to speak at home.

My parents were not unusual in that they were patriotic, they loved the homeland and place of their youth. When we saw depictions on television or I told them about things I was told in school that did not conform with their story, I was told what I was told was simply wrong.

My father did not like Jews. My mother cared less for Gypsies. One day, my mother directed my gaze toward an article in a large German volume, a dictionary, and in it were pictures of dozens and dozens of specimens of people of various races and ethnicities. We went through all the pictures until we found the picture of the Teutonic blonde. That’s who we were, I was told. And we were a “superior race.”

I was usually at the top of my class through primary school, so that might have confirmed the superior race presumptions of my parents, but I also knew in my early years that if I did not get top marks, I would be spanked. Learning came easily to me, but I also knew I needed to bring home those exceptional report cards to keep peace in the home.

I was not a natural racist however. Neither were my parents. As an insurance salesman, my father penetrated the Mohawk and Chinese communities. My mother made clay masks and stained glass work, because she was an artist, that mimicked the traditional arts of our First Nations communities here in Canada.

My favourite poet, growing up, was a Canadian Jew, Leonard Cohen. I still find myself sometimes reciting, “God is alive, magic is afoot…” My favourite musician was Jimi Hendrix whose Stars and Stripes absolutely transcended any version played in any stadium at any time.

I left home at sixteen, a disaffected racist. My first spiritual teacher was a Hindu swami. My second was Yogi Bhajan. I didn’t ask about their race.

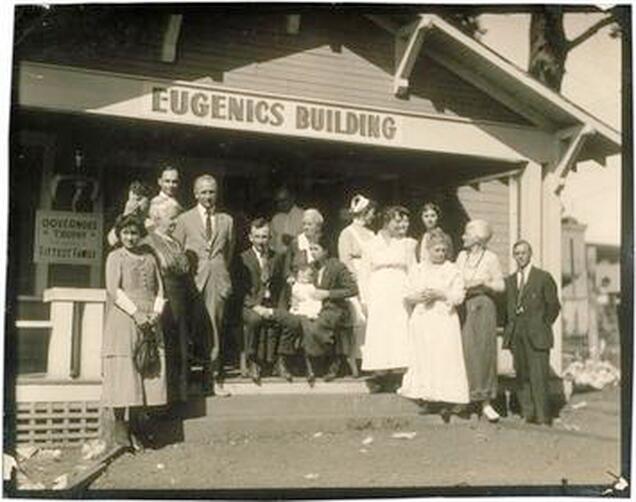

Over time, as I studied the roots of modern racism, I found the eugenics movement to have been very strong in the United States. People like Alexander Graham Bell, Theodore Roosevelt, and Margaret Sanger were all believers in genetic hierarchy before the idea caught on in Germany and Hitler put the idea to work in his “final solution” for the Jews. Lucky thing, it did not work out.

My parents were not unusual in that they were patriotic, they loved the homeland and place of their youth. When we saw depictions on television or I told them about things I was told in school that did not conform with their story, I was told what I was told was simply wrong.

My father did not like Jews. My mother cared less for Gypsies. One day, my mother directed my gaze toward an article in a large German volume, a dictionary, and in it were pictures of dozens and dozens of specimens of people of various races and ethnicities. We went through all the pictures until we found the picture of the Teutonic blonde. That’s who we were, I was told. And we were a “superior race.”

I was usually at the top of my class through primary school, so that might have confirmed the superior race presumptions of my parents, but I also knew in my early years that if I did not get top marks, I would be spanked. Learning came easily to me, but I also knew I needed to bring home those exceptional report cards to keep peace in the home.

I was not a natural racist however. Neither were my parents. As an insurance salesman, my father penetrated the Mohawk and Chinese communities. My mother made clay masks and stained glass work, because she was an artist, that mimicked the traditional arts of our First Nations communities here in Canada.

My favourite poet, growing up, was a Canadian Jew, Leonard Cohen. I still find myself sometimes reciting, “God is alive, magic is afoot…” My favourite musician was Jimi Hendrix whose Stars and Stripes absolutely transcended any version played in any stadium at any time.

I left home at sixteen, a disaffected racist. My first spiritual teacher was a Hindu swami. My second was Yogi Bhajan. I didn’t ask about their race.

Over time, as I studied the roots of modern racism, I found the eugenics movement to have been very strong in the United States. People like Alexander Graham Bell, Theodore Roosevelt, and Margaret Sanger were all believers in genetic hierarchy before the idea caught on in Germany and Hitler put the idea to work in his “final solution” for the Jews. Lucky thing, it did not work out.

Come about 1975, my Sikh teacher first challenged us, his mostly Caucasian students, to learn Punjabi, his mother tongue and to forge ties with the Punjabi community. Bibiji, his wife published a 3HO Punjabi Handbook with easy lessons to help us. Children were being sent to India where presumably they would pick up some of the language and culture. At the Khalsa Council, Yogi Bhajan’s preeminent administrative body, a resolution was passed that each member would give or read a short speech in Punjabi the following Baisakhi.

The reality of crossing the cultural divide between East and West and developing fluency in the Brown man’s language had already been brilliantly embodied by Bhai Sahib Dayal Singh. Meeting Yogi Bhajan for the first time in 1971 at the age of 15, Dale Sklar - as he was known then – fell in love with Sikh Dharma and devoted himself whole-heartedly to learning Gurmukhi – the scriptural language – and Punjabi – the spoken language. After a life-altering pilgrimage to India in 1973, Yogi Bhajan gave him the title and responsibilities of “Bhai Sahib,” which he cheerfully and humbly served until his sudden departure in a car crash in September of 1975. It is no wonder Yogi Bhajan said that God had then “picked the most precious flower from his garden.”

I was able to take a class with Bhai Sahib at Summer Solstice 1975. I also had a copy of Bibiji’s Punjabi handbook that I studied from time to time, but was never really able to make progress with any Indian language until I enrolled in university as a mature student and took a course in Hindi, as there were no Punjabi classes available. The classes and the course structure and the marking helped me to focus, and soon I was speaking Hindi which is not that different from Punjabi.

At the same time, feeling a deep attraction to the Sikh community, whose global reach was becoming more apparent to me as more and more immigrant Sikhs arrived in my home town of Toronto, I took up some meaningful work. Already, as a turbaned and white-clothed Caucasian, I was consciously circulating in society as a kind of magnet for the racists and bigots of my fine city – and I was well-suited for the job because my self-esteem was really impenetrable. Rather being cowed or shamed, I felt I was taking the venom from these poisonous lowlifes and making the society as a whole safer and somewhat more accepting for my newer and more vulnerable brothers and sisters in faith.

In 1977, taking my lead from some stories I had read about in our Beads of Truth magazine, I applied to join the Canadian army. It took a couple of years, and I passed the case on to a colleague so I could focus on my studies at school, but by 1979 Sikhs were allowed to serve in the Canadian Armed Forces. It felt pretty good. The next year, I did a similar case that paved the way for bearded Sikhs and orthodox Jews and Muslims to be able to drive a vehicle for a living without fear of discrimination. I became a little famous.

It felt nice. But in my heart, I felt something was missing. I missed Bhai Sahib’s carefree eloquence in Punjabi and Gurmukhi. And, living in Canada, I could not help wonder at how Sikhs from India would move to Montreal where both French and English are spoken, and learn both, while we 3HOers hung back with the excuse that “Punjabi is so hard to learn!”

“Are we Caucasians stupid or is there something more insidious at work here?” I wondered, already knowing the answer and determined to prove I was not stupid.

I started taking evening classes with a kindly gentleman. Avtar Singh was his name. He had been born in Pakistan before partition and could speak and write Punjabi, Urdu, Farsi, and – of course – English. I would visit him once a week as he patiently did drills with me and fed my curiosity about the treasury of the Guru’s languages.

If you know a bit of my personal story, you will know that by this time – around 1994 – I was fully engaged in writing Yogi Bhajan’s biography. It was not a money-making project and it took up most of my time, so it was with great surprise that I received a ticket for my first trip to India in September of 1995.

In Punjab was my first chance to really practice what Punjabi I had learned. It was a humbling experience, but I persevered. At the World Sikh Conference (Vishav Sikh Sammelan) that year, I could not help noticing as I passed out free glossy manuals about the meditative technology of the Shabad Guru, that many Punjabis asked for Punjabi versions, but there were none to be had. We 3HOers were largely mono-lingual English-speakers and they mostly spoke only Punjabi. It seemed like a vast chasm between us. But they smiled and graciously took our English manuals as souvenirs.

In Punjab was my first chance to really practice what Punjabi I had learned. It was a humbling experience, but I persevered. At the World Sikh Conference (Vishav Sikh Sammelan) that year, I could not help noticing as I passed out free glossy manuals about the meditative technology of the Shabad Guru, that many Punjabis asked for Punjabi versions, but there were none to be had. We 3HOers were largely mono-lingual English-speakers and they mostly spoke only Punjabi. It seemed like a vast chasm between us. But they smiled and graciously took our English manuals as souvenirs.

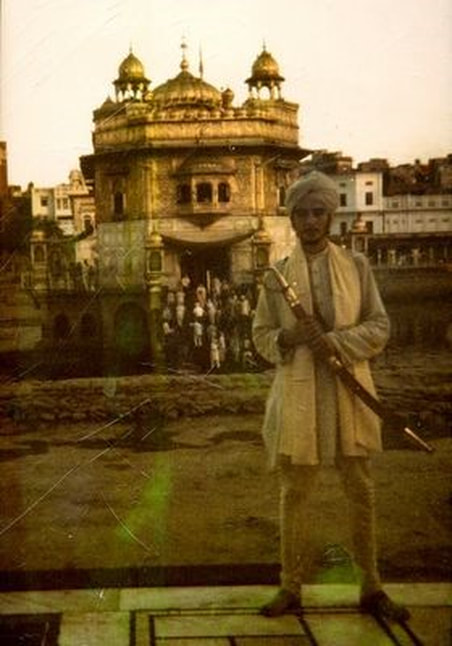

As it happened, after my stay at the rest house across from the Golden Temple (Harimandir Sahib) was up, I accepted the invitation of a jungle sadhu Sikh who had visited us at Guru Ram Das Ashram in Toronto. His name was Sant Baba Darshan Singh Kulewale and with his wooden staff, unconventional turban, and cotton stockings, he looked like some kind of Gandalf. He really had lived in the jungle with the wild animals in his younger years, but now he had a dayra (ashram) on the outskirts of Amritsar with an orphanage and a naturopathic medical dispensary.

Babaji did not speak a word of English, which forced me to really try my Punjabi around him. It was not for want of trying that Babaji would not speak English with me. He had taken a vow many years before, when the British where still running India, not to utter the language of the colonial oppressors – and he was keeping his vow.

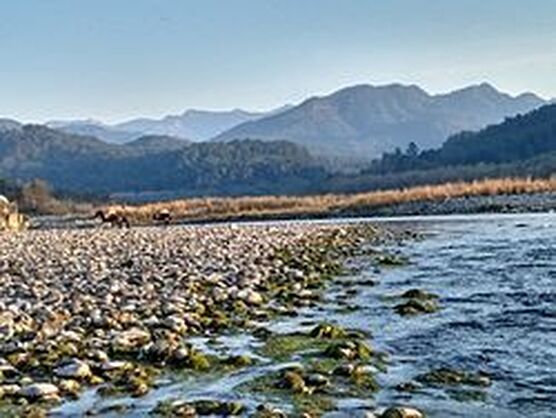

Babaji was very good to me. He treated me kindly and built me up in various ways. One time, a whole entourage of us packed up and began a two-day trip by truck into the foothills of the Himalaya where his devotees had founded a farming community, and each year – in that magnificent setting – there was a festival of the best Sikh story-tellers and preachers of India.

I reveled in the foothills and sunshine and fresh air of the community of Ajitpur, and the gracious hospitality of our hosts who were utterly kind and respectful. We got along in my simple Punjabi.

I did not pay too much attention to the preachers and story-tellers because their language was mostly beyond my level of understanding, but I could not help notice that the most famous Sikh teacher of all India, Giani Sant Singh Maskeen was on the program, and speak he did. He also had a sidekick, a fellow named “Louis Singh,” dressed all in black from head to foot. I had heard there was some prestige for an Indian preacher to have a Western following, so I guessed Louis Singh was Gianiji’s ornament.

It was something to watch Louis Singh in action as he addressed the congregation. For a half hour or so, they would sit in rapt attention as he spoke. By the end, a small mountain of rupee notes will have piled up as offerings on the stage before him and the Sangat would let loose a chorus of “Bolay So Nihaal! Sat Siri Akaal!” again and again. It was quite moving, especially considering the farmers did not understand a word of English and he did not speak Punjabi.

We exchanged a few words, we English-speakers – he all in black and me in white and gold - at the festival. Louis Singh asked if I was ex-3HO. I smiled inside and replied, “I am 3HO, why?”

On the second day, I received word that Baba Darshan Singh wanted me to give a talk on the next and final day of the festival. In my mind, I summoned up my best Punjabi and the next morning, I did my best sadhana. With all my heart, I wanted to honour my hard-working brothers in faith, these tillers of the earth. I wanted to speak to them intelligibly with the language of their heart – if only Guru Ram Das would allow it.

Well, the day came and the hour came and I took to the stage most humbly before a thousand or so wondering Sikhs. I am sure they were wondering who I was and what would I have to say. Of course, at that point, I was wondering too!

I started off with what I knew: “Aad Guray Nameh, Jugaad Guray Nameh, Sat Guray Nameh, Siri Gurdayvay Nameh…” Then in simple Punjabi, grade two level I imagine, I started to tell the story of Guru Nanak and how he trained Bhai Lehna so he would become fit to lead as the Second Guru, and how as Guru Angad, he trained and inspired Baba Amar Das until he was fit to succeed him as the Third Guru. A cadence was established and a logical rhythm, and I continued as the Sangat sat in utter silence, appreciating every word.

As the end of my short presentation approached, I explained how Guru Gobind Singh had passed the Guruship on to Siri Guru Granth Sahib and also on to the Khalsa. We were almost done our lesson of the day.

Then I gave that rapt congregation a little poke. You see, the whole while I had been their guest, they had identified me as “Angrayz” meaning Englishman. In perfect Punjabi, I said to them, “Mai Angrayz nahee(n).” (I am not an Englishman.) Then I poked them hard, provoking and confronting them with their worst ancestral nightmare, “Tusee(n) nahee(n) Hindoo.” (You are not Hindu.) Then the elevation set in: “Asee(n) Khaalsaa!” (We are Khalsa!)

The next moment is difficult to describe, though it remains forever engraved in my memory. It seems the heavens opened up. Guru Gobind Singh’s massive battle drum resounded. The eyes of a thousand Sikhs lit up in ecstasy and sheer spiritual delight. Whatever distance there might have been between us was shattered or revealed as a very hokey and inconsequential illusion. We were one! In the excellence of Khalsa, we were one! And, by the grace of God and Guru, we would forever be so…

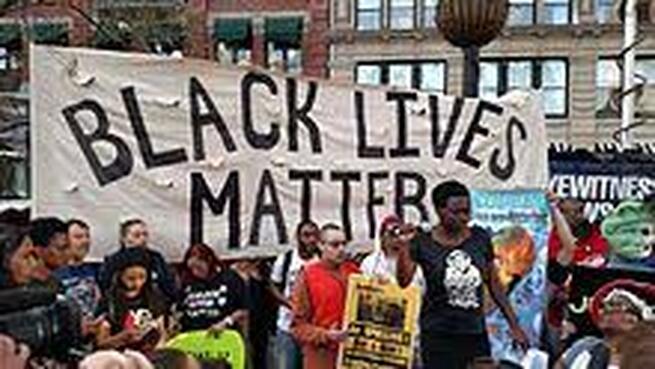

Twenty-four years have passed since that day. It is 2020 and racism is the topic of the day.

I am now convinced that we are not stupid, but there is something insidious that keeps most of us from picking up a Brown or Black or Red or Yellow language – while Yellow, Red, Black and Brown people the world over are learning English and French and Spanish by the billions.

I am an expert in this. I have told you how my parents told me I was a “superior German” and I did not believe them. And how I made it my mission to learn a Third World language partly because Yogiji wanted me to - and partly just to prove it to myself that I could.

It is not just laziness that keeps Whites from picking up Coloured languages. Do you think there are no lazy people successfully learning English this very minute? It is not laziness – and I expect you do not want to hear this - but it is exceptionalism, it is elitism, it is colonialism, it is racism that determines your behavior from deep inside of you.

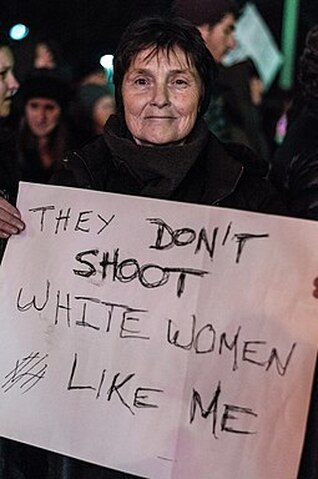

It is racism when you say to yourself that people of Colour should learn your language of colonial privilege and there is not a reason in the world that you should reciprocate and learn the beautiful cadences and secret gardens of their language in return.

That is not laziness. It is called “White privilege” – and you indulge in it because you know you can, because you know you can get away with it, because you know the cards in America and in many places in the world are still stacked against people of Colour and you are determined to play that Colour card just as long as you are able because you like it.

This is not the end of the world. But it might be the end of the world as you have known it if you are willing to accept the difficult truth of your own racist bias and how it restricts you, how it ties your heart in knots, how it poisons your love.

This is not the end of the world. But it might be the end of the world as you have known it if you are willing to accept the difficult truth of your own racist bias and how it restricts you, how it ties your heart in knots, how it poisons your love.

Black Lives Matter. Brown Lives Matter. Red Lives Matter. Yellow Lives Matter. Put them together, and they make up most of the people on the planet – by far. And that should not scare you.

It is an opportunity. It is an opportunity for growth. It is an opportunity of abolishing slavery. An opportunity of abolishing self-serving boundaries. It is an opportunity of realizing the very best in us. All of us. Giving all of us the chance to grow and be our very best – regardless of the colour of our skin, regardless of where we are born, regardless of our politics – left or right.

Now is the time. This time matters. It is time to give up tired, worn-out ways and embrace the new.

It is an opportunity. It is an opportunity for growth. It is an opportunity of abolishing slavery. An opportunity of abolishing self-serving boundaries. It is an opportunity of realizing the very best in us. All of us. Giving all of us the chance to grow and be our very best – regardless of the colour of our skin, regardless of where we are born, regardless of our politics – left or right.

Now is the time. This time matters. It is time to give up tired, worn-out ways and embrace the new.